Per capita food production is declining. The reasons for the decrease include:

- Decline in amount of arable land: We had been increasing the amount of farm land by clearing forests and irrigating dry land, but that strategy has reached a point of diminishing returns. Today we are paving over bountiful farm land and losing acreage in some areas to soil salinization and erosion.

- Green Revolution burnout: The great yield enhancements achieved through the use of chemical pesticides, fertilizers, and increased irrigation have peaked. In some cases, yields are starting to decline again.

- Collapse of ocean fisheries: Many ocean fisheries are near, or have, collapsed. Environmental problems like global warming are likely to exacerbate food production problems. The high levels of US debt and inherent economic instability will mean there won't be a lot of free-flowing cash available to fix these problems once they become more obvious to everyone.

THE U.S. IN 1950 |

THE U.S. IN 2005 |

| World's foremost oil producer and oil exporter |

World's foremost oil importer |

| World's largest exporter of machine tools and manufactured goods |

World's largest importer of manufactured goods, with manufacturing jobs now fleeing to other countries |

| Self-sufficient in nearly all resources |

World's foremost importer of non-petroleum resources |

| World's foremost creditor nation |

World's foremost debtor nation |

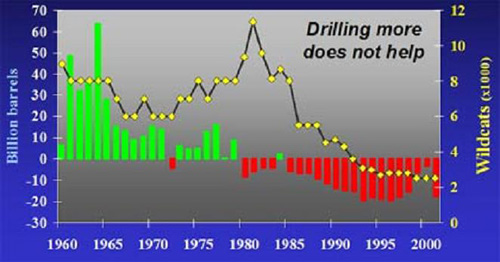

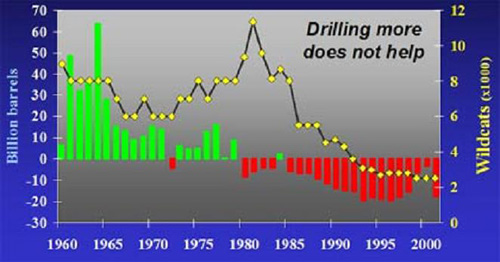

Net Oil Discovery Minus Production

Quoth the Maven

"We estimate that world oil and gas production from existing fields is declining at an average rate of about 4 to 6 percent a year. To meet projected demand in 2015, the industry will have to add about 100 million oil-equivalent barrels a day of new production. That's equal to about 80 percent of today's production level. In other words, by 2015, we will need to find, develop and produce a volume of new oil and gas that is equal to 8 out of every 10 barrels being produced today. In addition, the cost associated with providing this additional oil and gas is expected to be considerably more than what industry is now spending."

Jon Thompson

President of ExxonMobil

Exploration Company, 2003

The International Energy Agency (IEA), which is sort of the global equivalent of the US Department of Energy, tends to be very optimistic in its oil projections. But even they are predicting a future oil shock (officially they still say it is decades away). Some of the reasons they give for predicting a future oil shock are:

- We've already captured much of the "low-hanging" fruit (the "easy oil")

- Older oil fields are mature and declining;

- New discoveries are smaller fields;

- The oil industry is extracting oil from fields more quickly;

- More effort is being expended just to offset oil depletions;

- Global reserves have been overstated for political reasons.

Should we not be turning to a domestically-produced diesel?

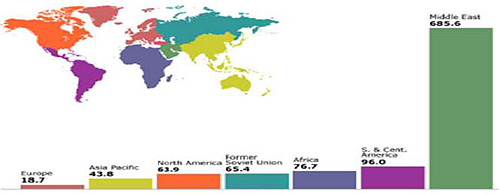

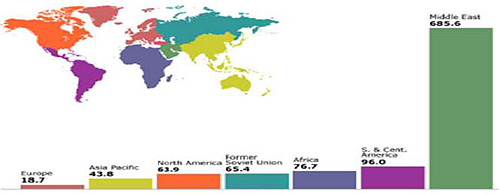

The bar for the Middle East's reserves should probably be about one-third shorter than it is due to overly optimistic statements of reserves from Middle Eastern OPEC nations (who overstate their reserves to be able to export more oil and still stay within OPEC rules).

But even given that, the Middle East still has a lot of the world's remaining oil.

The location of global oil reserves has much to do with political decisions today and in the future.

In late 1999, Dick Cheney, then chairman of the world's largest oil services company, Halliburton, spoke before the International Petroleum Institute in London.

He presented the following picture of world oil supply and demand to industry insiders:

"By some estimates, there will be an average of two percent annual growth in global oil demand over the years ahead, along with, conservatively, a three percent natural decline in production from existing reserves . . . That means by 2010, we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day."

When President Chirac gave [President] Bush a souvenir statue of the Eiffel Tower, Bush exclaimed:

This is great! A little oil rig!'

Jay Leno

Cheney has stated publicly that energy conservation may be a sign of personal virtue—but is not the basis for an energy policy. George W. Bush stated publicly, among other things, "That the US way of life is not negotiable."

This, apparently, is our energy plan going forward.

China is looking for long-term oil contracts in Central Asia, the Middle East and elsewhere. Saudi Arabia, interestingly, has given almost all of their recent long-term oil contracts to China rather than the US. As you can imagine, this has bothered some US-based oil companies.

Does the Saudi action have to do with the fact that China is not currently invading one of its neighbors?

Does it have to do with the Saudis having more faith in the Chinese economy?

We talked about record levels of US debt (much of it now held by China), record US trade deficits (much of it with China), and high levels of US dependence on imported oil, resources, as well as manufactured products. There is a strange sort of dance of mutual dependence and competition playing out between China and the US, but what happens once we hit the other side of peak oil, when there is no longer enough oil to meet the demands of both economies?

The current investment pattern of �a billion dollars here and a billion dollars there for alternative-energy research and for things like tax credits so people will put solar panels on their roofs" won't get us there.

We need to be investing hundreds of billions of dollars a year to develop the technologies necessary to overcome our dependence on vanishing fossil fuels. Overall, this effort will require the investment of trillions of dollars.

Unfortunately, this is not on the drawing boards.

THE FIX IS IN

"Will there be some sort of technological fix:

the hydrogen economy, methane hydrates, or car makers suddenly producing a car that gets 200 miles per gallon? Perhaps, but I wouldn't want to bet on that."

Richard Heinberg

This is a challenging picture. The majority of Americans probably won't change or even listen. But we need a small, core portion of society that understands the reasons for the tough things that are going to be happening over the next decades, and that understands how to respond.

If these people can start dealing with the problem in their own lives and can start making changes in their local communities, they can teach others. Then there is hope.

(Richard Heinberg is widely acknowledged as one of the world's foremost Peak Oil educators. A journalist, educator, editor, lecturer, and a Core Faculty member of New College of California where he teaches a program on "Culture, Ecology and Sustainable Community.")